Today is an exciting day. Not long ago, my wife returned home with a trunk full of books: the legendary World Book Encyclopedia. This was the reference material of my childhood, and my first point of contact when I found myself plagued with questions, insomnia, or snow days. If it wasn’t in The World Book, it probably wasn’t worth knowing.

Today is an exciting day. Not long ago, my wife returned home with a trunk full of books: the legendary World Book Encyclopedia. This was the reference material of my childhood, and my first point of contact when I found myself plagued with questions, insomnia, or snow days. If it wasn’t in The World Book, it probably wasn’t worth knowing.

I learned about all sorts of things here: how cheese is made, why soap works, how cars are manufactured, where kindergarten came from, why alternating current is chosen over direct current for distribution over long distances. Some time after I left home, my parents gave the encyclopedia to another family.

These days, unless I’m doing research for an academic paper, most of my questions are answered here, or here. The Internet has changed everything. I’m an advocate for Wikipedia, even in [some] academic settings: after all, the organic and community-reviewed site’s accuracy has been compared to Encyclopædia Britannica. And why not? Culture and language is in constant transition. Technology and research progress and are distributed so quickly that the value of printed reference material, from encyclopedias to dictionaries, might been called into question. If I’m at the grocery store, and I feel a sudden urge to know more about the business practices of Nabob, I can find the information I need. Instantly. If I’m lying awake in bed, wondering what the creepy insects showing up near the back door are, I can find out. Instantly. These things can, and do happen. Often.

But truth be told, I’ve been after a set of World Books for some time. Why? Chalk it up to age, nostalgia, and my new role as a parent: books like these were important to me, and I hope that on some level, I can share them with young Eben as he grows up. But it would be naïve for me to to think that the 1986 World Book Encyclopedia could play the same role in his life that it did in mine. I knew that, as I carried them into the house. And I knew that, as I flipped through a few volumes, recalling some of the articles and photographs from the world of my youth: “Automobile,” displaying a Datsun 280ZX; “Soviet Union,” see Russia; “Russia,” a Communist dictatorship of 15 Union Republics; “Chernobyl,” no entry. Really?

In the 1987 Year Book, I found a black-and-white photograph, and a one page article titled “Explosion at Chernobyl”.” And what I already knew became crystal clear: these books captured one point of view from a moment in time. And while they will be useful for teaching my son about reading and learning, as well as topics like stars and bugs, entries like the ones listed above will need to be interpreted through the lens of “the world my dad grew up in.” What a young Jesse Dymond once considered catalogues of knowledge have become history books. Useful, but not in the same way. Because it’s not 1986. Perhaps our natural desire to hold these records and experiences up as permanent vessels of that elusive thing we call truth is a form of idolatry?

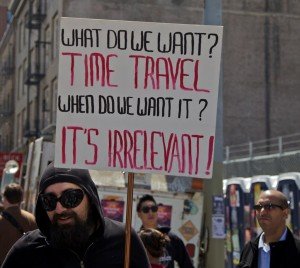

I find myself wondering about our desire to cling to everything from ideas to interpretations, language to liturgy, style to song. The Church is no stranger to moments in time, and rightly so: we relive the last supper almost every time we gather (incidentally, using a prayerbook from 1985). We’re about to move into a season of watching and waiting for Christ’s birth in our world. And these are wonderful moments. Ancient moments. Moments in time that hang in the mystery of already-but-not-yet here. Moments for which time is irrelevant.

I find myself wondering about our desire to cling to everything from ideas to interpretations, language to liturgy, style to song. The Church is no stranger to moments in time, and rightly so: we relive the last supper almost every time we gather (incidentally, using a prayerbook from 1985). We’re about to move into a season of watching and waiting for Christ’s birth in our world. And these are wonderful moments. Ancient moments. Moments in time that hang in the mystery of already-but-not-yet here. Moments for which time is irrelevant.

What do you think? Are some traditions and resources obsolete, and dubiously passed on to the next generation? Are others timeless? How do we know the difference?